Understanding AI in an Era of Great Power Politics

Minimizing the regulation of AI would empower the United States, but it must protect its democratic values and civil liberties.

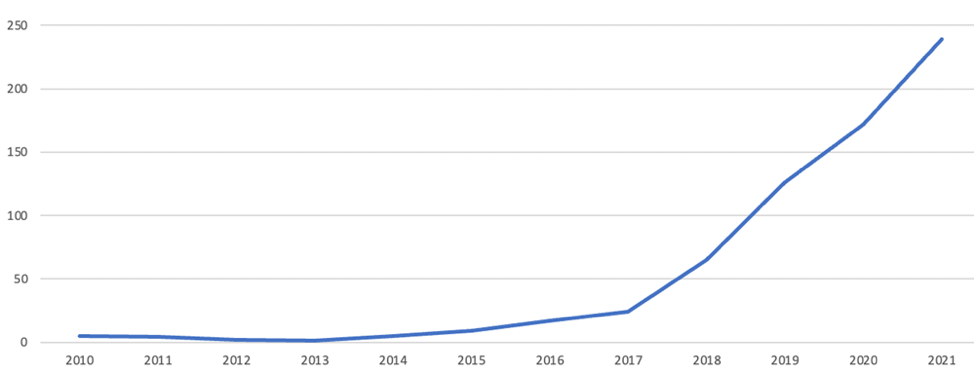

As cyberattacks grow exponentially—an insecure computer can suffer 2,000 attacks per day—Artificial Intelligence (AI) is now imperative to deal with the massive volume of breaches. Yet, it seems that AI developers and researchers are behind the curve. Namely, the number of AI developers eclipses those that deal with its safety thirty to one. Moreover, AI-focused cybersecurity solutions only rose after 2016.

Figure 1: Annual distribution of research papers presenting a novel AI for cybersecurity solution

As governments are increasingly under pressure to both deploy and regulate AI, policymakers need to understand what types of AI are available for cybersecurity purposes. As Max Smeets wrote: “Discussing the use of AI in cyber operations is not about whether technology or humans will be more important in the future. It is about how AI can make sure developers, operators, administrators, and other personnel of cyber organizations or hacking groups do a better job.” Policymakers are hungry for sound academic advice clarifying the political and legal implications of a complex and complicated technology.

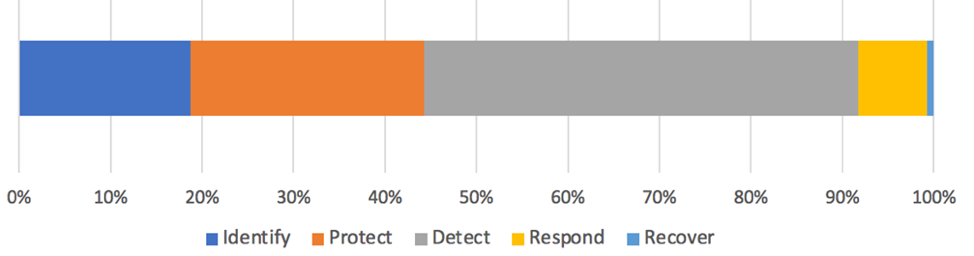

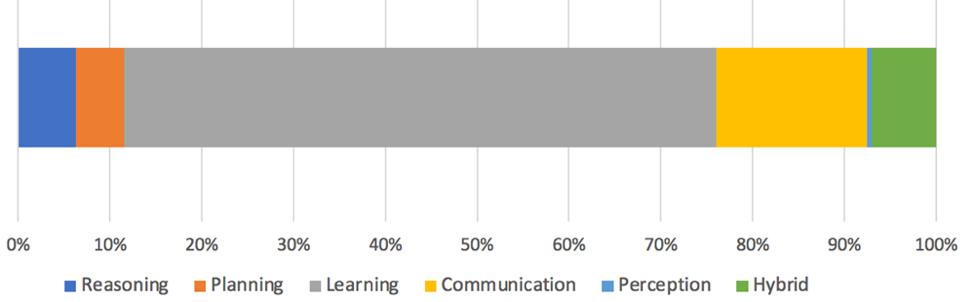

Thus, we offer a foundational overview of the use cases of AI for cybersecurity. Namely, we look at the publicly available unique AI algorithms (700) and use a rudimentary NIST (National Institute of Standards and Technology) framework to determine for what cybersecurity purpose (identify, protect, detect, respond, or recover) distinct types of AI algorithms (reasoning, planning, learning, communications, or perception) are being used.

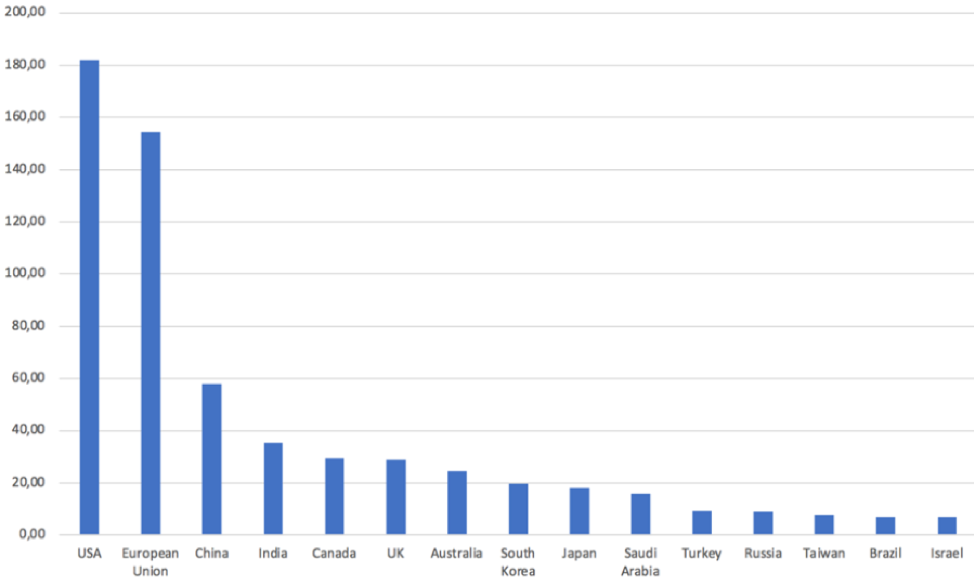

First, we dispute findings that only looked at the sheer number of publications, as we look only at novel AI solutions for cybersecurity. Hence, when one takes this deeper perspective, one sees that it is not China that leads the way in developing AI for cybersecurity, but rather the United States. The majority of the authors are affiliated with institutions within the United States or the European Union.

Figure 2: Geographic distribution of research papers presenting a novel AI for cybersecurity solution

Second, analyzing 700 unique AI for cybersecurity solutions according to the five NIST categories, we see that 47 percent of them focus on detecting anomalies and cybersecurity incidents. The second most popular category, with 26 percent, is protection, followed by identify and respond, 19 percent and 8 percent, respectively. This comes as a surprise as we see a gradual shift towards Cyber Persistent Engagement Strategy: comparing the U.S. National Cybersecurity Strategy of 2018 and 2023 or comparing the development of EU member-states strategies, political initiatives, and rhetoric.

Figure 3: Distribution of research papers presenting a novel AI for cybersecurity solution according to the cybersecurity purpose

There are several dimensions in answering this puzzle. Cyber Persistence Theory does not map well onto the NIST framework, as the latter does not include anticipation—a key feature of Cyber Persistence Theory. The latter “redefines security as seizing and sustaining the initiative in exploitation; that is, anticipating the exploitation of a state’s own digital vulnerabilities before they are leveraged against them, exploiting others’ vulnerabilities to advance their own security needs, and sustaining the initiative in this exploitation dynamic.” Hence, linking Cyber Persistence Theory to response within the NIST framework distorts its meaning. Furthermore, states are risk-averse, and letting machines decide when and how to respond to a cyber-incident might be too escalatory, similar to self-driving cars, where the liability considerations are too high for such vehicles to be operational. Finally, AI models need a lot of training data before they can be deployed. However, appropriate data to prepare a response AI cybersecurity algorithm is scarce.

Third, less surprising is the distribution of AI algorithms developed for cybersecurity according to their nature. Almost two-thirds of the AI-based cybersecurity solutions use learning methods (64 percent), followed by communication (16 percent), reasoning (6 percent), planning (5 percent), and a hybrid format, using a combination of the two or more aforementioned methods—7 percent.

Figure 4: Distribution of research papers presenting a novel AI for cybersecurity solution according to the nature of the AI algorithm

When we cross-tab both dimensions—the purpose and the nature—of a unique AI solution for cybersecurity, we see that machine learning algorithms dominate all five cybersecurity functions. They are primarily used for intrusion and anomaly detection, malicious domain blocking, data leakage prevention, protection against distinct types of malware, and log analysis.

Curiously, we have also found that some well-known cases of AI applications for cybersecurity do not have many unique AI algorithms developed—e.g., penetration tests and behavior modeling and analysis. Future research should indicate if this is due to the satisfactory performance of the existing ones, so much so that there is no demand for new ones.

Cyberspace and AI are both means and platforms for great power politics. As both are rapidly evolving, regulation may, in fact, unintentionally lead to overregulation, as lawmakers cannot guess the direction of the rapid development. In turn, overregulation would have a damp effect on the development and deployment of digital technologies. Hence, minimizing the regulation of AI in cyberspace would empower the United States and give it an edge in global power politics. However, the United States must also find a way to safeguard its democratic values, norms, principles, and civil liberties when dealing with these new technologies. Therefore, transparency guidelines are in order for the ethical use of AI for cybersecurity, as well as strengthening public oversight of the intelligence and security agencies’ use of AI in cyberspace.

Igor Kovač is a researcher at The Center for Cyber Strategy and Policy at the University of Cincinnati and The Center for Peace and Security Studies at the University of California, San Diego. His research focuses on the intersection between political economy and security studies. He served as the foreign policy advisor to the Slovenian Prime Minister from 2020 through 2022.

Tomaž Klobučar is the head of the Laboratory for Open Systems and Networks at the Jozef Stefan Institute. His main research areas are information security and technology-enhanced learning.

Ramanpreet Kaur is a researcher at the Jozef Stefan Institute.

Dušan Gabrijelčič is a researcher at the Jozef Stefan Institute.